Keywords: South Korean culture, Jeju island, asian literature, Haenyeo, WWII Jeju, historical fiction, past-present storyline

Genre: Historical fiction

Length : short medium long

Country: South Korea

Review

“Here is a secret: Long long time ago, when I was a girl, I was a mermaid, too.”

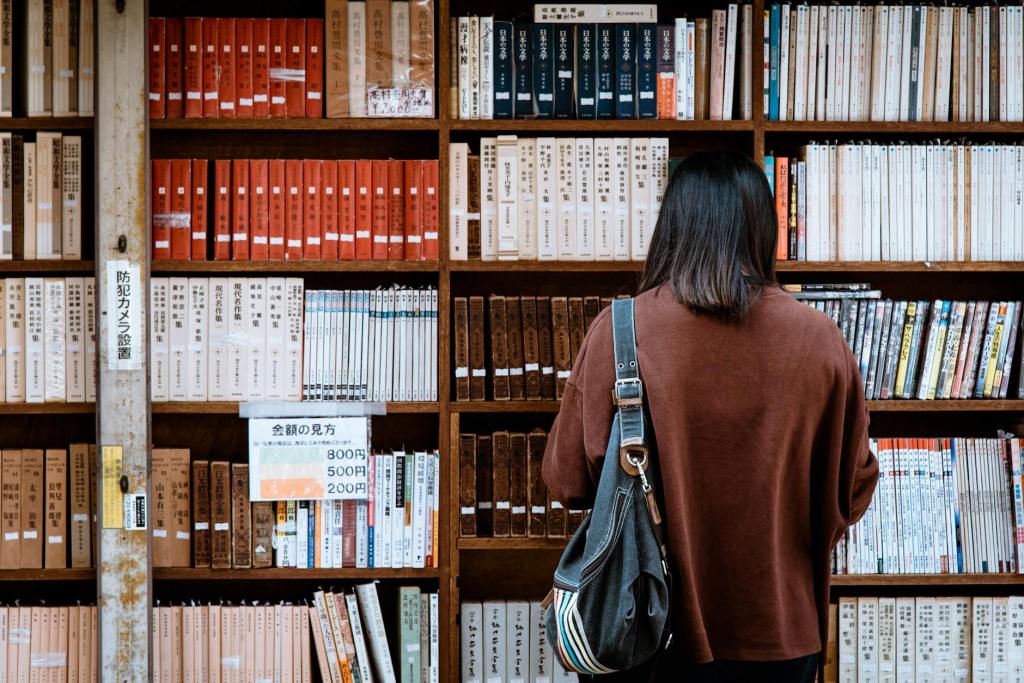

So, if you’re like me, you must have stumbled upon Lisa See’s books. Books like The Island of Sea Women, which, in all honesty, was exquisite. It was an amazing, emotional, sensitive, empathetic, historical book that left you and me thirsting for more stories about haenyeo and about Jeju. Now, when I saw the title of this book, The Mermaid from Jeju, obviously, I knew it was talking about haenyeo and not mermaids, real mermaids. So, I picked it up, very excited, with lots of hopes, and really thinking that I’d get a story centered on the divers.

But everything goes a bit differently.

We take a deep dive into our main character’s life, from youth to old age and even death, and we see Jeju Island in the years just after World War II, around 1948. That was an unstable, turbulent time: Japanese troops had just withdrawn, U.S. troops came in, and political instability was everywhere. The story really begins when Junja, the daughter of a haenyeo, wants to take the abalone across Mount Hallasan to trade for pork. Normally her mother would make this yearly trip, but Junja decides it’s her turn to step into responsibility. On the way she meets Yang Suwol, a mountain boy — and you can already guess where that’s going. At the house where she trades, she discovers the woman there is actually her mother’s close friend. Suddenly, Junja feels guilty for having taken her mother’s place on the trip, realizing that by doing so, she may have stolen her mother’s chance to see her friend.

When she returns home, tragedy strikes: her mother has drowned while diving. At first, everyone believes it was an accident, but gradually we see the broader picture — political upheaval, ideological battles, arrests, and social turmoil creeping even into Junja’s family.

One of the strongest aspects of the book is how it deals with grief, loss, and memory through a Jeju lens — not “Korean” in general, but specifically Jeju culture, with its own customs, dialect, and worldview. I especially liked seeing how Junja navigates her grief, the tragedies that keep piling up, her sudden marriage, and the complicated family dynamics. Hierarchy, relationships, status, generational ties — all of it is filtered through Jeju’s cultural perspective, which makes it both fascinating and deeply specific.

“The half moon disappeared behind a cloud, casting the scene into darkness. The silence between the boy and girl expanded. It filled with memories of promises made, words that the world had broken”.”

Added there’s the role of nature and place. The island, the sea, and Mount Hallasan aren’t just background; they’re characters in themselves. The novel captures how landscape shapes not only beliefs — shamanism is woven in here — but also politics and violence. Mountains and valleys aren’t just mystical places, they’re also strategic ones, battlegrounds for every upheaval. That interplay of spirituality and geopolitics through the land itself was done beautifully.

“Tendrils of vine and fern fell from both sides of the gully, like green waterfalls spilling from rocks. Sunlight beamed through the trees, illuminating every tiny insect and mote in the air…”

I also appreciated that this book doesn’t treat “historical fiction” as just “fiction set in the past.” Instead, it engages with history head-on. The Jeju April 3rd Incident — a real mass killing and suppression — is built into the novel. The ideological battles, the arrival of U.S. influence (even visible in food culture: Jeju food, Seoul food, American food), and the brutal repression are all embedded into the story. Before reading, I knew nothing about these events, and I left with a clearer sense of what Jeju endured.

That’s the good news. And this occupies about 65–70% of the book.

The second part? Not so much.

The narrative suddenly jumps into a “back-to-present” structure. We land in 2001, then get dragged back into the past through reminiscences, so you’re in the present but really still in the past. On paper, it’s meant to tie loose ends together and bring closure, but the execution left me more confused than enlightened. Listening to the audiobook only made it worse: I struggled to keep track not of names, but of when I was. The first half flowed perfectly; the second half kept wobbling between timelines.

And frankly, I don’t enjoy that sort of narrative trick. Pick a time period and stick to it. The author had built a world of families, community, and people I cared about, and then she abruptly tossed me into another timeline with a new cast. Just as I got my bearings, we were shoved back to the past again. It undercut the emotional weight of the first half. Yes, the revelations matter, and yes, the story gets its closure, but the structure drained the impact for me.

Overall? The writing itself is beautiful, and the first half is excellent. But if you’re here for haenyeo stories, go read The Island of Sea Women and be very happy. If you’re determined to read everything about Jeju’s divers, sure, pick this up — just don’t expect the best. I landed on three stars out of five. Not a “do not recommend,” but definitely a “think twice.”

And because I don’t want my blog to be just glowing reviews of perfect books — tastes differ, after all — I’m leaving this one here. Who knows, maybe it’ll turn out to be your cup of tea. Let me know if it is.

Leave a comment